Scientific Thinking and Avoiding Avalanches #2: Use Evidence

Note: This is the second installment in a series of posts on using scientific thinking for avoiding avalanches. The first post was on using a method (system).

Evidence is the available body of information indicating whether a belief is valid. It is the basis for drawing conclusions in both science and avalanche safety. Using evidence rather than dogma, popular opinion, or tradition is what sets science apart from pseudoscience and religion (Stock 1985).

Gathering evidence for a scientific study is a spectrum from observing things as they appear in nature, to formal experiments (tests). For example, a psychologist may use GPS units to track skiers and observe their decisions. Or a snow scientist may use a cold lab to test crystal change. In both examples it's collecting all evidence, and not just picking evidence that supports their beliefs.

Evidence and data-driven decisions are ideal, but it’s up against our culture, values, and beliefs. For example, much of the nation supports an administration that is anti-science and selects evidence against vaccination, and the role of humans in climate change, etc. Similarly, when backcountry skiing, we may notice red flags indicating the snow could avalanche, but if we value skiing in avalanche terrain, we may select evidence and ignore those red flags.

Our disregard for evidence and science may be because the human brain doesn’t think in data; we think in stories (Aschwanden 2024). Anecdotes—short stories—are concrete, understandable, and how we’ve historically learned and still learn. Stories from people we respect, such as avalanche mentors, can teach us valuable lessons that we don’t forget, but they should be used with caution. Anecdotes are single pieces of evidence, not consensus. They ignore the law of large numbers and regression to the mean (Ahn 2022).

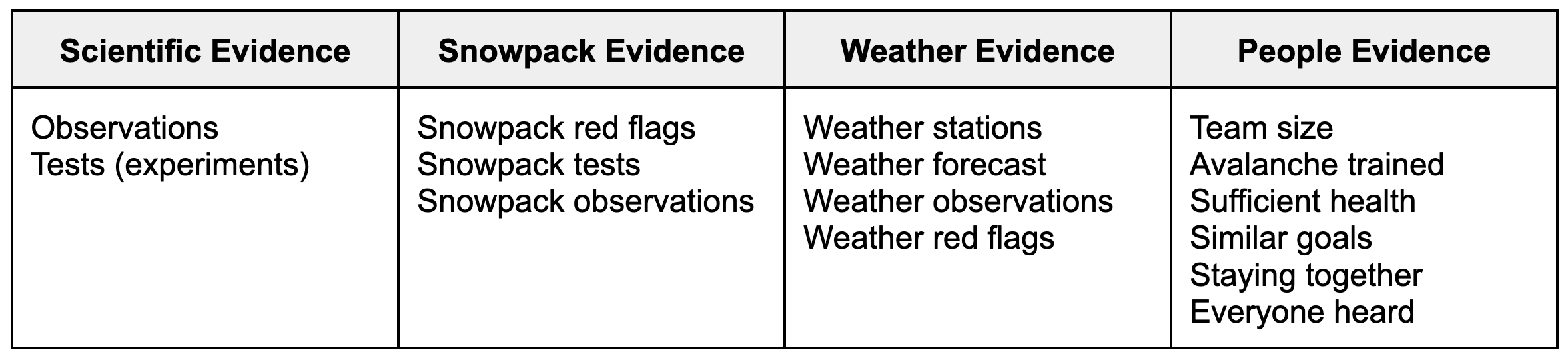

When backcountry skiing, before going out to ski, we gather evidence about conditions—snowpack, weather, people—and then choose safer terrain to travel. Once in the backcountry we continue to gather evidence about conditions.

Gathering evidence is the basis for drawing conclusions in science and avalanche safety.

Collecting evidence from multiple sources (triangulation), and having those findings converge and support each other, strengthens research findings, makes them more trustworthy, and less biased. In the backcountry, when different lines of evidence converge—e.g., from the avalanche forecast and field observations—the conclusions are strengthened and we make more objective avalanche decisions

“When we are in a situation without seeing avalanches or getting collapses we are in a data poor environment. That’s why I think it’s so important to dig! ”

References

Ahn, Woo-Kyoung. 2022. Thinking 101.

Aschwanden, Christie. 2024. Uncertain, Scientific American. scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/uncertain-a-new-podcast-series-on-the-joys-of-not-knowing/

Stock, Molly. 1985. A Practical Guide to Graduate Research.