Scientific Thinking and Avoiding Avalanches #3: Strive to be Objective

Science should be objective as possible so it represents the evidence and improves our knowledge. Strive for objective evidence. The problem is, science is done by humans, and humans are biased. For example, scientists work hard, and want to find interesting results to their questions, so they may omit results that do not produce interesting results. Funding from private industry may bias scientists, such as the tobacco industry arguing against cancer, or the oil industry arguing against climate change. Further biasing science is the paradigm and culture in which the scientists work, such as ignoring traditional avalanche knowledge that may accept fate in favor of controlling nature (e.g. remote avalanche control systems).

A known source of bias in avalanche science is the lack of diversity; the field is dominated by white males (Mannberg and others 2025). For example, the committee for ISSW 2024 was all males in the physical sciences. Diversity in science brings a range of views, and greater epistemic strength (Oreskes 2021).

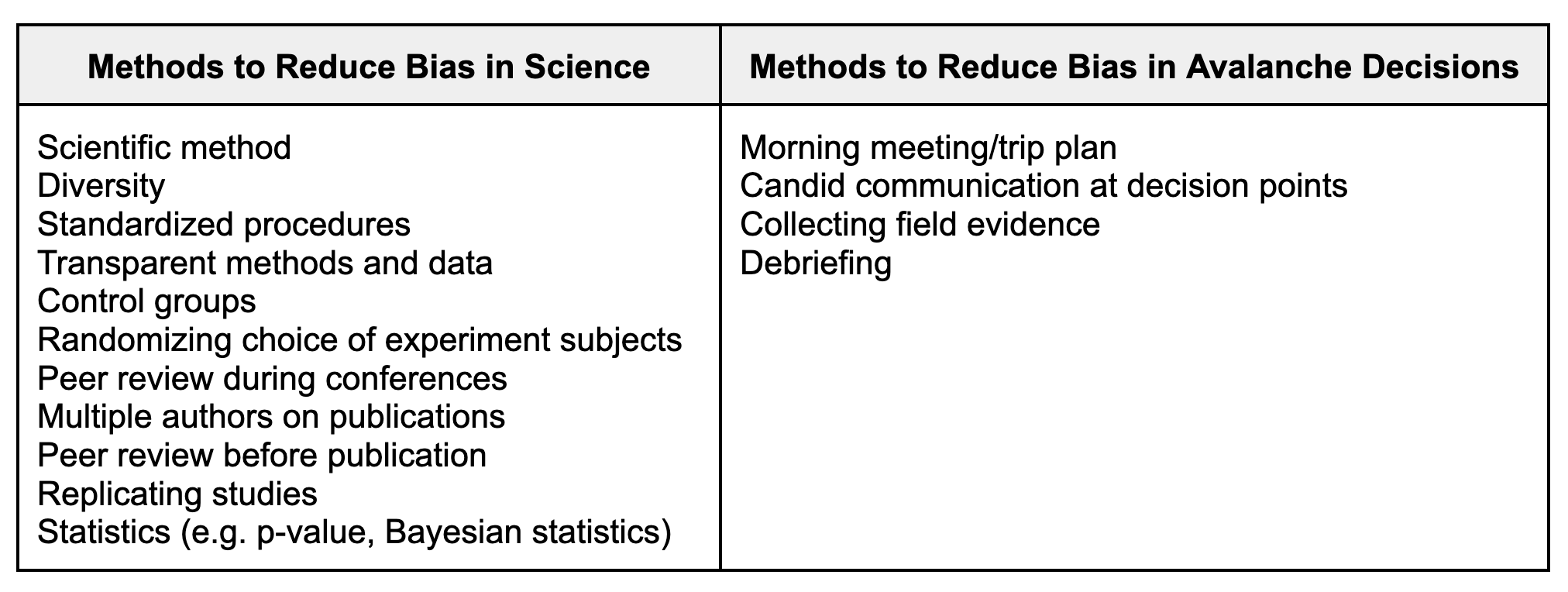

To reduce bias, and be more objective, science imposes a ruthless structure of self-policing that pervades the method and culture. For example, statistics, when used objectively, help show the relationship between variables and give a degree of validity about the evidence (e.g. p-value). Before publication, studies are subjected to informal peer review during conferences and in conference proceedings. When submitted for publication, a peer-reviewed journal sends a draft to a selection of expert reviewers who help identify potential shortcomings. Also, the study methods are explained in the publication so others can assure the scientific method was used.

Both science and avalanche safety have established methods to reduce bias.

Like science, backcountry skiing is packed with opportunities for bias; confirmation bias, anchoring bias, sunk cost bias, and all other known biases. As emotional humans, who love to ski in avalanche terrain, we are ripe for bias. The evidence may show us that the snowpack is unstable, but that evidence is overridden by our desire to ski powder in avalanche terrain. Also, snow rewards bad decisions because slopes usually don't avalanche, even during elevated avalanche conditions, so we learn the wrong lessons, which increase our bias, and leaves us less objective. Since simply being aware of our biases doesn’t help, avalanche professionals put systems in place to reduce biases such as choosing good partners, trip planning in the guide meeting, slowing down, and collecting evidence.

The tricky dichotomy when striving for objectivity is that opinion is needed. A good scientific paper concludes with the scientist speculating on the meaning of the results and giving suggestions for further research. When backcountry skiing, members must give their opinion to contribute to the team.

References

Mannberg, Andrea; Johansson, Maria; and Latosuo, Eeva. 2025. Exploring the Gendered Landscape of the Avalanche Safety Industry, Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism.

Oreskes, Naomi. 2019. Why Trust Science?